Perth Concert Hall

reviewed by Neville Cohn

Over decades, I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve listened to Haydn’s Symphony I04 in D minor. It is one of the glories of the classical era – and the Australian Chamber Orchestra was the ideal ensemble to give point and meaning to this supreme utterance. Much of the performance – whether in moments of high drama or introspection – bordered on perfection, leaving this critic in the rare and pleasant position of having to do little more than sit back and acknowledge artistry at a consistently impressive level.

Over decades, I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve listened to Haydn’s Symphony I04 in D minor. It is one of the glories of the classical era – and the Australian Chamber Orchestra was the ideal ensemble to give point and meaning to this supreme utterance. Much of the performance – whether in moments of high drama or introspection – bordered on perfection, leaving this critic in the rare and pleasant position of having to do little more than sit back and acknowledge artistry at a consistently impressive level.

There were also two premieres: Movements (for us and them) by Samuel Adams and A Knock One Night by the indefatigable Elena Kats-Chernin, the latter’s new work in turn dramatic, sinister, occasionally charm-laden and quirky – and, as with all her work, instantly accessible.. Adams’ piece is music of a very different stripe, often dark in mood and tone, music suggestive of anger, fear and confrontation expressed in torrents of notes.

In Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No 1, Steven Isserlis, as ever, brought formidable ability to bear on his stunningly complete account of the work. Behind the printed note lurks an anguished demon – and Isserlis revealed it to the nth degree, presenting the cello line in the first movement with an impassioned, searing intensity that brooked no opposition. At its most intense, there was about the performance an urgency that drew me to the edge of my seat. The lengthy cadenza (which is the concerto’s third movement) was a model of what impeccable cello playing is all about.

Much hair flopping and facial contortion were a distraction but, as in the past, looking away from the soloist on-stage enables one to savour to the full the near-matchless quality of Isserlis’ profoundly meaningful playing. Shostakovich’s concerto is one of the most disturbing works he ever produced – and it takes a soloist such as this and an orchestra of highest calibre to encompass its daunting terrain in so complete a way – and so do full justice to the work. An avalanche of thoroughly deserved applause prompted an encore, Isserlis playing Song of the Birds, a Catalonian folk song made famous by the legendary Casals and here offered in an arrangement for unaccompanied cello.

Isserlis played on the superb Nelsova Stradivarius of 1726 on loan to him from London’s Royal Academy of Music – and he is worthy of it.

A lavish bouquet in particular to Premsyl Vojta, that master of the French horn. His contributions were like a golden thread through the evening.

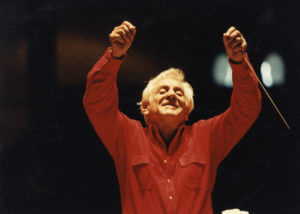

If, as a result of unavoidable circumstances, I’d come very late to the WASO’s concert at the weekend and managed to listen to only the last work on the program, I’d have gone home well satisfied. Leonard Bernstein’s Symphonic Dances from West Side Story was a sonically incandescent offering with irresistible rhythms, thrilling responses from the brass players and with those in the WASO’s bustling “kitchen department” in particular. delivering a sizzlingly effective conclusion to the evening. This was the orchestra at its focussed best.

If, as a result of unavoidable circumstances, I’d come very late to the WASO’s concert at the weekend and managed to listen to only the last work on the program, I’d have gone home well satisfied. Leonard Bernstein’s Symphonic Dances from West Side Story was a sonically incandescent offering with irresistible rhythms, thrilling responses from the brass players and with those in the WASO’s bustling “kitchen department” in particular. delivering a sizzlingly effective conclusion to the evening. This was the orchestra at its focussed best. I have been attending – and reviewing – WASO concerts for more than 35 years.

I have been attending – and reviewing – WASO concerts for more than 35 years.