Perth Symphonic Chorus

Armistice Choir

Perth Philharmonic Orchestra

Perth Concert Hall

reviewed by Neville Cohn

It could not have been a more solemn occasion: a performance devoted to the fallen in World War I exactly one hundred years to the day

since the curtain finally came down on a hideously prolonged battle that saw the death and disablement of millions.

As we listened to The Ode of Remembrance and bugler David Scott playing The Last Post, there was a minute of almost palpable silence to reflect on the

slaughter that was World War 1. Then, as the Australian national anthem was sung by the choirs and a capacity audience, the thoughts of most would surely have focussed on the dreadful events of the years 1914 to 1918. Significantly adding to the memorial atmosphere was the fact that the 4pm start of the concert coincided with 9am in France, that being 100 years to the hour since the Armistice was announced by Prime Minister Clemenceau of France – and the concert’s end at 6pm coincided with the cessation of hostilities in France precisely 100 years before.

Then, Faure’s Requiem, its inherent melancholy revealed to a degree I cannot recall experiencing before. And it was listened to in an almost reverential silence.

Dr Pride has devoted her life to choral training and performance – and in this account of Faure’s masterpiece, the Requiem moved me as never before – no mean achievement given I’ve long lost count of the number of times I’ve listened to the work. From first note to last, Pride, as ever in complete control of her forces, did wonders, coaxing responses which brimmed with the sort of insights that come from a lifetime’s association with the setting. And the Requiem worked its melancholy magic as never before.

Violins, of course, do not feature in the work, their absence giving the string complement a rather darker sonic quality, wholly in keeping with the mood of the work. Soprano Sara Macliver was in her element here. She sang most movingly, again and again taking up an interpretative position at the emotional epicentre of whatever she sang. What a precious musical asset this soprano has been over the decades, not only to Perth but Australia as a whole. Christopher Richardson, too, sang with consistent expressiveness and a very real understanding of the text uttered so clearly – but from time to time rather higher decibel levels might to advantage have allowed his voice to be more emphatically projected towards the rear of the venue.

Millions of the armed forces died in this dreadful war. But there were other deaths, too – of animals ranging from homing pigeons and dogs to horses, each involved in the war effort. The most famous from an Australian perspective was the charge of the 4th Light Horse Brigade which captured Beersheba from the Turks. So it was entirely appropriate that, early in the program, a horse was ushered on-stage: Indie, rider Phil Dennis from the Kelmscott – Pinjarra 10 Lighthorse Troop. Indie, behaving impeccably, munched carrots.

Also on a memorable program was Vaughan Williams’ Dona Nobis Pacem.

What would most office workers do when it’s time to leave for the day? I imagine some might head for a drink at the nearest watering hole or perhaps do some hurried shopping for dinner before walking to a train station, bus stop or parking garage to head home. But the people who run Perth Symphony Orchestra came up with another possibility: offering city workers the chance to listen to a symphony concert before going home – and getting a little handy advice on yoga relaxation techniques for good measure.

What would most office workers do when it’s time to leave for the day? I imagine some might head for a drink at the nearest watering hole or perhaps do some hurried shopping for dinner before walking to a train station, bus stop or parking garage to head home. But the people who run Perth Symphony Orchestra came up with another possibility: offering city workers the chance to listen to a symphony concert before going home – and getting a little handy advice on yoga relaxation techniques for good measure. As was customary in Mozart’s day, the orchestra played standing (other than the cellists, of course). Audience seating was arranged around the orchestra, the players casually garbed in blue jeans and white tops. And from first note to last, there was about the playing a disciplined commitment which augurs well. Laurels, in particular, to the cellists and flautist; their contribution was particularly pleasing. The same could be said of the horn and trumpet players who were much on their mettle.

As was customary in Mozart’s day, the orchestra played standing (other than the cellists, of course). Audience seating was arranged around the orchestra, the players casually garbed in blue jeans and white tops. And from first note to last, there was about the playing a disciplined commitment which augurs well. Laurels, in particular, to the cellists and flautist; their contribution was particularly pleasing. The same could be said of the horn and trumpet players who were much on their mettle. He was a horrible person. He treated women appallingly. His vanity was exceeded only by his vanity. He was ferociously anti-semitic – but never hesitated to appoint top-flight Jews to interpret his music when he needed them. So he was a hypocrite as well. Wagner also engaged in the German revolution of 1848-1849). He took part in the Dresden uprising and had to flee the country when a warrant for his arrest was issued. But he was, as well, a genius, a composer of unique and profound operas. And this was breathtakingly in evidence at the Concert Hall on Sunday when Asher Fisch presided over an account of Tristan and Isolde, presented in concert version.

He was a horrible person. He treated women appallingly. His vanity was exceeded only by his vanity. He was ferociously anti-semitic – but never hesitated to appoint top-flight Jews to interpret his music when he needed them. So he was a hypocrite as well. Wagner also engaged in the German revolution of 1848-1849). He took part in the Dresden uprising and had to flee the country when a warrant for his arrest was issued. But he was, as well, a genius, a composer of unique and profound operas. And this was breathtakingly in evidence at the Concert Hall on Sunday when Asher Fisch presided over an account of Tristan and Isolde, presented in concert version. Over decades, I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve listened to Haydn’s Symphony I04 in D minor. It is one of the glories of the classical era – and the Australian Chamber Orchestra was the ideal ensemble to give point and meaning to this supreme utterance. Much of the performance – whether in moments of high drama or introspection – bordered on perfection, leaving this critic in the rare and pleasant position of having to do little more than sit back and acknowledge artistry at a consistently impressive level.

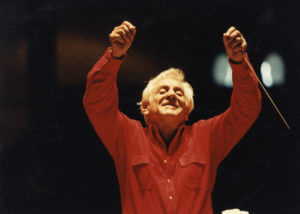

Over decades, I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve listened to Haydn’s Symphony I04 in D minor. It is one of the glories of the classical era – and the Australian Chamber Orchestra was the ideal ensemble to give point and meaning to this supreme utterance. Much of the performance – whether in moments of high drama or introspection – bordered on perfection, leaving this critic in the rare and pleasant position of having to do little more than sit back and acknowledge artistry at a consistently impressive level. If, as a result of unavoidable circumstances, I’d come very late to the WASO’s concert at the weekend and managed to listen to only the last work on the program, I’d have gone home well satisfied. Leonard Bernstein’s Symphonic Dances from West Side Story was a sonically incandescent offering with irresistible rhythms, thrilling responses from the brass players and with those in the WASO’s bustling “kitchen department” in particular. delivering a sizzlingly effective conclusion to the evening. This was the orchestra at its focussed best.

If, as a result of unavoidable circumstances, I’d come very late to the WASO’s concert at the weekend and managed to listen to only the last work on the program, I’d have gone home well satisfied. Leonard Bernstein’s Symphonic Dances from West Side Story was a sonically incandescent offering with irresistible rhythms, thrilling responses from the brass players and with those in the WASO’s bustling “kitchen department” in particular. delivering a sizzlingly effective conclusion to the evening. This was the orchestra at its focussed best. I have been attending – and reviewing – WASO concerts for more than 35 years.

I have been attending – and reviewing – WASO concerts for more than 35 years.