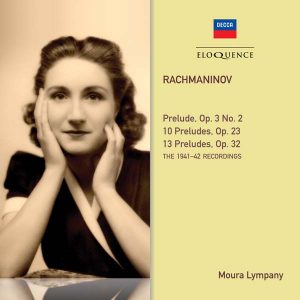

Prelude opus 3 no 2; 10 Preludes opus 23; 13 Preludes opus 32

Moura Lympany (piano)

DECCA 482 6266 (2CD)

TPT: 76’ 42”

reviewed by Neville Cohn

She was christened Mary Johnstone – but because the name sounded too ordinary for an on-stage career, Miss Johnstone became Moura Lympany, the surname an altered version of her mother’s maiden name. And she was – and will ever be – the only musician to have recorded the complete piano preludes of Rachmaninov on, firstly, 78rpm discs, then on LP and, finally, on CD.

She was christened Mary Johnstone – but because the name sounded too ordinary for an on-stage career, Miss Johnstone became Moura Lympany, the surname an altered version of her mother’s maiden name. And she was – and will ever be – the only musician to have recorded the complete piano preludes of Rachmaninov on, firstly, 78rpm discs, then on LP and, finally, on CD.

All the 78rpm recordings were made at DECCA’s West Hampstead studios during WWII. It was often a stressful experience. Editing out errors was not possible on 78 rpm discs. It was all-or-nothing.

If there was a slip of the finger, smudged pedalling, a fluffed note, a loss of momentum – a lapse of any sort – the prelude would need to be recorded again from scratch. At one particularly frustrating session, not a single prelude was deemed good enough for preservation. Sometimes, all would go well, at other times, a piece would sound below par and needing to be recorded again and again (and yet again) if considered necessary. It says much, then, for Lympany’s abilities that there’s not a dull moment; every piece sounds fresh and newly minted.

During the Blitz – like fellow pianist Dame Myra Hess in Hampstead – young Moura would take shelter beneath her grand piano in the event of a Luftwaffe bombing raid. There were so many terrible happenings during these horror years. One morning in May, 1941, for instance, Moura, on her way to Queen’s Hall to record Cesar Franck’s Variations Symphoniques, found, to her horror, that the hall had taken a direct hit, leaving a pile of rubble.

True, some of her later recordings of these works have greater depth, others are approached in slightly subtler ways – but they all bear the stamp of distinction.

Throughout, Lympany sounds utterly in control, again and again surmounting with ease the sort of technical hurdles that would cause lesser players to throw their hands up in despair. Some more about hands: Rachmaninov’s were enormous and he wrote music to take advantage of this – to the despair of musicians with smaller hands.

It is 76 years since Lympany’s Rachmaninov recordings first came on the market. They have weathered well. Brash, lilting, aggressive, sensuous, gentle, melancholy, introspective, suave – these and a myriad other moods are summoned up by a musician at the peak of her skills.

Stephen Siek’s liner notes are first rate. They make engrossing reading.