WAAPA Music Auditorium

reviewed by Neville Cohn

It is one of Western Australia’s most meaningful musical success stories.

It is one of Western Australia’s most meaningful musical success stories.

For years. Defying Gravity has brought performances of the highest order to invariably full houses. This is a particularly remarkable achievement in that, firstly, the performers are still students and, secondly, that the make-up of the ensemble constantly changes as WAAPA students graduate and take their skills to an ever-widening audience. And Tim White, percussionist par excellence, shares, as ever, a priceless understanding of the medium with his students.

Overwhelmingly, works on offer are of recent vintage so it was with particular interest that we listened to a work dating as far back as 1695 when King Louis XIV occupied the French throne. Here, on two timpani, Jesse Vivante brought a sense of high occasion to Philidor’s Batterie de timbales. This was an impressive and stylish summons to attention.

Moving forward 323 years, Germaine Png and Gabrielle Lee did wonders on vibraphone and marimba in Emmanuel Sejourne’s Losa. In high style, this young duo did wonders in evoking the essence of the music. Much of the playing was informed by a frankly delightful peekaboos insouciance and engaging rhythms.

Jonathan Jie Hong Yang’s Rainforest was given its world premiere performance. A program note refers to the music’s ‘mesmerising tranquillity’ – and 16 players pooled their skills to charming effect in evoking this gentle mood. In contrast to these islands of quietness, there were more emphatically stated ideas that fell most agreeably on the ear. I’d very much like to listen to this again, a view probably shared by most of the audience if the intensity of applause that greeted its conclusion is anything to go by.

In Steven Rush’s Mas Fuente, ferocity was well to the fore with savage attacks on drum surfaces and much energetic use of cymbals. A good deal of the performance was informed by a savage, unyielding intensity – but there were also moments where softer tones provided some aural relief.

If the name Pavan Kumar Hari meant little to concertgoers who thronged the auditorium, world premiere performances of three of his works involving both music and dance will almost certainly ensure his name is well remembered – and for all the best reasons. The middle work – Vichara – played on the vibraphone by the composer provided a charming interlude separating the dance offerings.

I am not in any sense an authority on traditional Indian dance styles which were a significant component of Hari’s Svatantrya and A Little Touch of India but to my uninformed eye, the dancing was fascinating and gripped the attention from the moment performers entered the darkened auditorium from different points while carrying small trays of tiny, lit candles which were deposited on the perimeter of the stage. Then followed dance episodes of grace and power that were both fascinating and satisfying. They were strikingly costumed.

Of particular quality were Shweta Baskaran’s accompaniments on sitar and Sivakumar Balakrishnanl on tabla.

Defying Gravity players positioned behind the dancers brought additional sonic muscle to the proceedings. Bravissimo!

What would most office workers do when it’s time to leave for the day? I imagine some might head for a drink at the nearest watering hole or perhaps do some hurried shopping for dinner before walking to a train station, bus stop or parking garage to head home. But the people who run Perth Symphony Orchestra came up with another possibility: offering city workers the chance to listen to a symphony concert before going home – and getting a little handy advice on yoga relaxation techniques for good measure.

What would most office workers do when it’s time to leave for the day? I imagine some might head for a drink at the nearest watering hole or perhaps do some hurried shopping for dinner before walking to a train station, bus stop or parking garage to head home. But the people who run Perth Symphony Orchestra came up with another possibility: offering city workers the chance to listen to a symphony concert before going home – and getting a little handy advice on yoga relaxation techniques for good measure. As was customary in Mozart’s day, the orchestra played standing (other than the cellists, of course). Audience seating was arranged around the orchestra, the players casually garbed in blue jeans and white tops. And from first note to last, there was about the playing a disciplined commitment which augurs well. Laurels, in particular, to the cellists and flautist; their contribution was particularly pleasing. The same could be said of the horn and trumpet players who were much on their mettle.

As was customary in Mozart’s day, the orchestra played standing (other than the cellists, of course). Audience seating was arranged around the orchestra, the players casually garbed in blue jeans and white tops. And from first note to last, there was about the playing a disciplined commitment which augurs well. Laurels, in particular, to the cellists and flautist; their contribution was particularly pleasing. The same could be said of the horn and trumpet players who were much on their mettle. He was a horrible person. He treated women appallingly. His vanity was exceeded only by his vanity. He was ferociously anti-semitic – but never hesitated to appoint top-flight Jews to interpret his music when he needed them. So he was a hypocrite as well. Wagner also engaged in the German revolution of 1848-1849). He took part in the Dresden uprising and had to flee the country when a warrant for his arrest was issued. But he was, as well, a genius, a composer of unique and profound operas. And this was breathtakingly in evidence at the Concert Hall on Sunday when Asher Fisch presided over an account of Tristan and Isolde, presented in concert version.

He was a horrible person. He treated women appallingly. His vanity was exceeded only by his vanity. He was ferociously anti-semitic – but never hesitated to appoint top-flight Jews to interpret his music when he needed them. So he was a hypocrite as well. Wagner also engaged in the German revolution of 1848-1849). He took part in the Dresden uprising and had to flee the country when a warrant for his arrest was issued. But he was, as well, a genius, a composer of unique and profound operas. And this was breathtakingly in evidence at the Concert Hall on Sunday when Asher Fisch presided over an account of Tristan and Isolde, presented in concert version. Over decades, I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve listened to Haydn’s Symphony I04 in D minor. It is one of the glories of the classical era – and the Australian Chamber Orchestra was the ideal ensemble to give point and meaning to this supreme utterance. Much of the performance – whether in moments of high drama or introspection – bordered on perfection, leaving this critic in the rare and pleasant position of having to do little more than sit back and acknowledge artistry at a consistently impressive level.

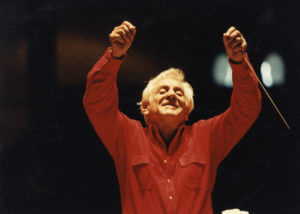

Over decades, I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve listened to Haydn’s Symphony I04 in D minor. It is one of the glories of the classical era – and the Australian Chamber Orchestra was the ideal ensemble to give point and meaning to this supreme utterance. Much of the performance – whether in moments of high drama or introspection – bordered on perfection, leaving this critic in the rare and pleasant position of having to do little more than sit back and acknowledge artistry at a consistently impressive level. If, as a result of unavoidable circumstances, I’d come very late to the WASO’s concert at the weekend and managed to listen to only the last work on the program, I’d have gone home well satisfied. Leonard Bernstein’s Symphonic Dances from West Side Story was a sonically incandescent offering with irresistible rhythms, thrilling responses from the brass players and with those in the WASO’s bustling “kitchen department” in particular. delivering a sizzlingly effective conclusion to the evening. This was the orchestra at its focussed best.

If, as a result of unavoidable circumstances, I’d come very late to the WASO’s concert at the weekend and managed to listen to only the last work on the program, I’d have gone home well satisfied. Leonard Bernstein’s Symphonic Dances from West Side Story was a sonically incandescent offering with irresistible rhythms, thrilling responses from the brass players and with those in the WASO’s bustling “kitchen department” in particular. delivering a sizzlingly effective conclusion to the evening. This was the orchestra at its focussed best. I have been attending – and reviewing – WASO concerts for more than 35 years.

I have been attending – and reviewing – WASO concerts for more than 35 years.